Welcome back. In Part 1, six well-known writers gathered to discuss the subject of violence in art. The 'chat' attracted more than 4000 readers. Today the knights have reassembled to joust with the final five questions.

The secret is to create a character with sufficient depth that you're fascinated by him/her, even if he's a monster. Hannibal is compelling because he's so damned multi-faceted and real seeming. In my own work, the super assassin El Rey is a cold-blooded killing machine, but he's also really interesting and 3D. The trick to making a killer or monster whom we'll follow is to imbue him with qualities that force the reader to turn the page to find out what he's going to do next, and to care.

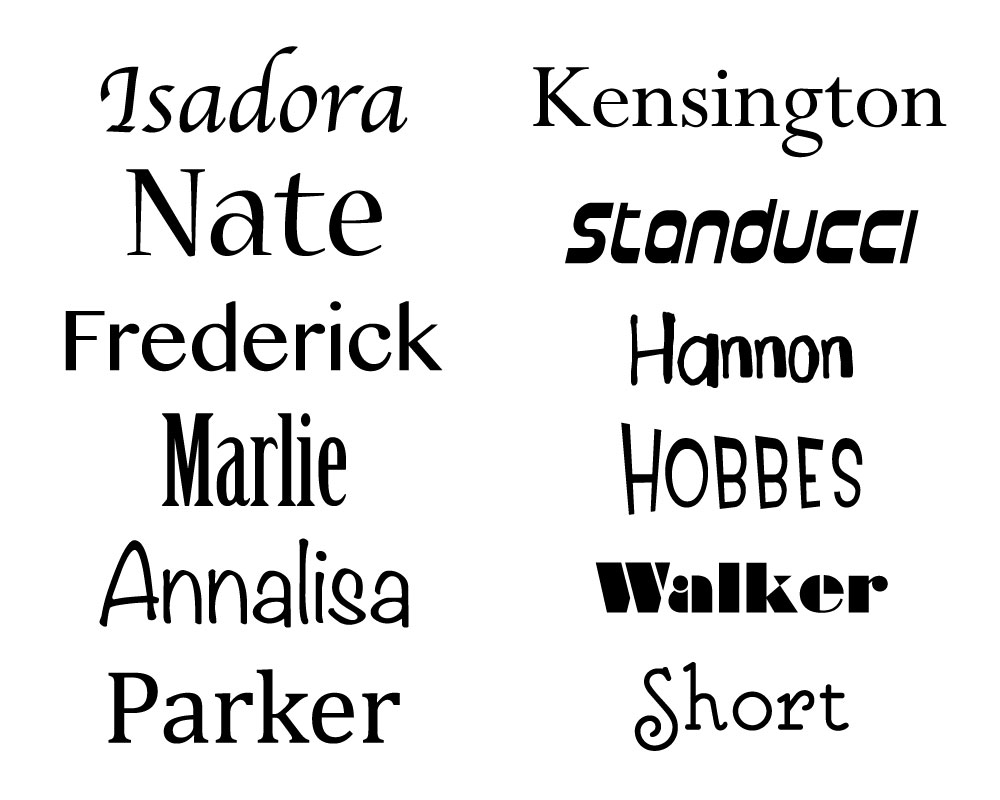

Bouchard

I’ll respond to this in terms of my own writing and can easily zero in on wit. After all, who wants a killer who doesn't have a sense of humor? If there’s one thing I enjoy when my wife is giving a new work of mine a first read, it’s hearing her suddenly burst out in laughter. When this happens, it’s generally because she’s reading a scene where the killer made some hilarious comment while in the process of dealing with a soon-to-be victim. Nobody can say my killer isn't a funny guy… and he’s also polite.

Butts

For characters like Hannibal or Dexter, I think it is a blend of all three with a little bit of wish fulfilment as well. These characters get to do what most of us wish we could do: destroy our enemies in the most gruesome, cathartic manner possible. These guys do horrible things, yes, but they don’t do them indiscriminantly. Their victims, for the most part “deserved” it: Hannibal is our id destroying those who hurt our pride through insensitivity or rudeness, Dexter is our avenging angel who exacts gory justice on those evildoers who manage to slip through the cracks of our justice system.

Kirton

I think you've covered it--charisma, charm, wit. But it's the sort of question where input from women (writers and readers) would be interesting. My answer to question 8 may explain in part why I say that. From my male perspective, if I ever do find myself captivated by a character who's inflicting harm or worse on someone else, I feel guilty. Fortunately, it doesn't happen very often. I suppose if it were a vigilante wreaking vengeance on a pedophile or someone who;d killed or harmed friends or family, the moral dimension would make it acceptable, even desirable. But if the intention is to appall or excite in the name of entertainment, then I think there needs to be some corrective. There's already a shortage of empathy in the world and to accept tacitly that it's OK for one individual to abuse or obliterate another is to add to the inhumanity quotient.

There are exceptions. Violence, in Tom Sharpe's early novels, was so extreme that its effects were comic. It occurred in contexts which weren't intended to convey realism, and whose characters went to caricatural extremes. The 'sadism' of Patrick Bateman was different. It was simply part of a general lifestyle (shared by others in the novel) and helped, symbolically and powerfully, to convey the notion that society's values have changed and we're losing our humanity.

And yet, venturing into such areas is part of what writers do. As Baudelaire put it, we should 'go into the depths of the unknown to look for something new.'

Logan

I'm reminded of Lee Marvin in the 1967 film,

Point Blank, directed by John Boorman (and based on the novel,

The Hunter, by Donald E. Westlake). Marvin, as Walker, has been double-crossed and left for dead. Walker has been betrayed by his wife and best friend. He sets out to exact revenge, but als to regain the precise amount of money that has been 'stolen' from him, $93000. It becomes almost comical, throughout the film, when Walker comes up against adversaries who cannot believe he would be creating such mayhem for 'only' $93000, which to the adversaries is small change. But to Walker, this is the figure he has decided on as his own 'valuation' in life. Walker does terrible things, but we know why, and the brutal simplicity of his goal lures the view into sympathizing with the insane purposefulness that drives Walker (even down to one film critic who saw the purposefulness manifested in Walker's actual way of walking in the film when the camera lingers on his pavement-whacking shoes.)

So, perhaps not charisma, charm, or wit finally...but instead a deadly earnest intent, a pursuit of a definite purpose or goal, this is something we can relate to, even find ourselves inspired by, even if we do not agree with that goal objectively.

It may be important also that Marvin brought real WW2 experience of violence to his onscreen roles.

For a literary example of making the unpalatable palatable, Jim Thompson's novels, on the other hand, often told from the viewpoint of the psychotic, unreliable narrator, manage to achieve fascination by representing the shocking twists and turns of an innately wild and feral state of consciousness, which becomes enthralling to the reader just because of this very alien-ness, The readers cannot bring themselves to look away and miss the next unpredictable event or thought.

Strickland

I can think of a few possibilities. First, yeah, the trope that good women love bad men has truth in it--and for both genders there's the Byronic appeal of a character who gives not one solitary faint damn for the restrictions of social convention and the law. Let's face it, some actors also just have that element of self-assurance, of delight in their own power and control, that might make us wish we could be a Cagney, or even a manipulative Karloff or a suavely sinister Vincent Price Same holds true for the women, of course--the best of the bad girls could make men think, "Man, I'd like to tame her" and women think "You go, girl!" Helena Bonham Carter can take such pure glee in mayhem that it's hard not to root for her; that sweet mermaid Daryl Hannah was incredibly stylish as cold-blooded assassin Elle Driver; and I have to, just have to, put in a good word for Margaret Hamilton, whose Wicked Witch of the West treasured her 'beautiful wickedness.' It's hard not to admire such single-minded, driven characters--thanks to the actors who give them life.

Even so, most of us, I think, have the sense to know that it's better to daydream about being such a character than setting out to follow the actual career path, though. "Interesting responses, and your test scores are impressive. So if you go with our firm, where do you see yourself in five years?" "Oh, drenched in other people's blood and cackling maniacally."

Still, reading about such characters, or seeing them on screen, lets the audience release tensions, disperse their accumulated bad humours, and reach what Aristotle called a catharsis--though that literally means puking. Some part of the human psyche loves to be titillated and teased with beyond-the-pale behavior. Stephen King wrote somewhere that reading about such horrors is our way of feeding the gators, keepin' 'em down in the cellar where they can't really hurt us, and he has something there.

Then too--well, 99% of the time, a rollercoaster's a safe ride, innit? You're not expecting that the gawky kid in the car ahead will jump up and be decapitated at the top of the second hill, or that the heavy woman two cars back will suffer a coronary, or that a freak wind will blow a high-tension wire across the tracks and send ninety bazillion volts through you...And that never happens.

Well, hardly ever.

Similarly, we're seated in our coaster cars when we read or watch violent actions. Eyeballs pop and frizzle, blood flows like champagne (which, as is well known, flows like water), carnage ensues...but not for US. We're safe on our comfy butts there in the coaster car, riding the rails of our imagination, and on some level we know that. Exposing our imaginations to the worst that humans can do to humans--that's running up and flat-hand slapping the front door of the Boo Radley place, it's dropping a clattering gold cup while plundering a snoozing dragon's hoard, it's the good old boy at the wheel next to you saying "Hold may beer 'n watch this!" It's a scare that we enjoy, somehow--all the more so since we know we're really safe. Mostly safe.

7) All-out hardcore gore fests--e.g. 2000 Maniacs (1964)--appeal to extreme horror fans while outraging gentler souls. Still, a film or book that wants it both ways--extreme violence for profits and a moral message for approval--seems even more offensive. (E.g., a splatter film which the hit man pauses between kills to brood on the bad things he's done and is about to do again.) Can you think of a book/film perfectly combining graphic violence with either a strong theme or moral center?

Blake

Sure. Easy.

Rambo. Innocent everyman taken on by a corrupt system and serving up a ten course meal of whup ass. Although

No Country For Old Men is hard to beat for graphic violence with a strong theme (greed ultimately backfires and thus is bad).

Bouchard

I have never been a fan of horror or gore so books and films portraying extreme graphic violence have never appealed to me. Defined, graphic violence is the depiction of especially vivid, brutal and realistic acts of violence in visual media. I consider this definition does not imply the obligation to include blood and guts beyond what may be required to realistically portray any given scene.

That said, and considering film and television have not been a large part of my life for several years, the first film which came to mind upon reading this question is Spielberg’s 1971

Duel. The film is an extremely realistic depiction of good overcoming evil against all odds in the classic David and Goliath genre. Though no heads explode, nor are any bodies ripped apart, one cannot deny this movie’s violent content. A 1955 Peterbilt does make for a rather nasty weapon.

Butts

Anything by Cormac McCarthy, especially

No Country for Old Men, which uses its violence to underscore the horrors of growing old, or

The Road, which uses violence to illustrate what a thin veneer of civility our social structure provides us and to show how easy it would be to revert back to savages (a theme I think

Walking Dead plays around with quite effectively as well).

Kirton

I’m struggling here and my first thought was ‘No, I can’t’. On the other hand, some of the things that are happening in the world today convey extremes of violence on one side which seem counterbalanced by righteous indignation on the other. If that’s how the world is, there must be films and books which convey it. And, in fact, these events are presented to us as narratives by journalists and spokespersons of the various factions. But the convenient way in which they divide protagonists into good guys and bad guys is misleading. The killing of hostages, the suppression of beliefs opposed to one’s own, even the posting of death threats on Twitter – in nearly all cases, the perpetrators think what they’re doing is ‘right’; it fits their morality, furthers their cause and beliefs. In the field of morality there are no global absolutes. When diametrically opposed moralities clash, there can be no redemption.

And how about the Greek tragedies? All those wives, sons, mothers, fathers killing one another to avenge a son, sister, mother, father – all doing so at the behest of one or other of their Gods and finding, as a result, that they’re cursed by another. It seems you can please all of the Gods some of the time or some of the Gods all of the time. But you can’t please all of the Gods all of the time.

Logan

Several come to mind.

Sam Peckinpah’s

Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid successfully presents the film’s graphic violence in a context of eulogy, to a time and place long vanished, and to a wild, free way of life on the 1881 Western frontier about to be permanently regulated and curtailed by the new forces of law and order, heralded in by the external imposition of power by the wealthy New Mexico cattle barons.

An interesting counterpoint to this is the later film,

Three Days of the Condor, set in a 1975 of CIA shenanigans and looming oil shortages, a time where that nascent frontier law and order has hardened and warped into an edifice perhaps worse than the lawlessness which preceded it, and where the hunted Robert Redford character can no longer tell where American law and order ends and corporate business interests begin.

Another great 1975 genre film is Walter Hill’s

Hard Times, which shows Charles Bronson’s Chaney character fighting with his fists, for survival, and for his next meal…in a 1930s Depression-era America which will allow him no other way forward.

Strickland

Macbeth, or course—the slaughter of the innocents, Duncan weltering in his own gore, Macbeth hopelessly realizing he’s waded so far in blood that he might as well forge ahead and hope to reach the other side . . . his wife losing her mind and—maybe—taking her own life, leading to his crashing realization that he’s done all his dirty work for her. . . for nothing, now! And tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow creeps in this petty pace to the last syllable of recorded time, and life’s a walking shadow, a mere actor who says his lines and then vanishes from the stage; life is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury and signifying—nothing!

You can’t even hear the devil laughing.

That is bleak. It’s fully as bleak as

Waiting for Godot, a more modern theatrical take on cosmic indifference to human suffering. All the violence, all the excesses, lead Macbeth to ask a despairing question: What is the point of it all? The work reminds us to be aware not only of our desires and ambitions, but of the world around us. Some characters in the play are honorable and worthy of respect. One lad dies a hero’s death and his own father says he cannot mourn because he is proud of the boy. But Macbeth himself is ignominiously slaughtered, beheaded, and made a shameful public spectacle after his death. The play

Macbeth tells us that if the universe has no point for our lives, it’s up to us to make a point for ourselves—and we don’t do that by letting ourselves become monsters.

King Lear is even bleaker,

8) Do you have a violent scene you've been tempted to write for years--but which you fear is just 'too much'? Do you dare to tell us about it?

Blake

Not really. My first passes on

Fatal Exchange were pretty graphic but I softened them on drafts. Same for some of

King of Swords--what first went on the page had me wincing, but I quickly discovered that the audience that bought

American Psycho wasn't buying my books, and the graphic stuff was unnecessary, and in fact harmful, to sales. So I stopped writing to shock the reader and focused on entertaining them. If the characters and stories are compelling, there's no need to shock 'em.

Bouchard

To be blunt, no, I don’t. As I mentioned in the previous question and during our first round, violence for the sake of violence is not my style or forte so I've never been compelled to write anything more vicious than I actually did for any particular scene. While working on Thirteen to None, the eighth of my series, I sometimes had the impression some scenes were more violent than those in my previous works but was never uncomfortable with the results as they were required to paint the portrait I wanted to present to my readers.

Butts

I don’t really. I grew up reading Raymond Chandler and Richard Monaco as well as Stephen King, so I had very little idea that violence (or sex for that matter) were any kind of taboo subject for writing. My problem has always been describing them realistically. I have written three major fight scenes, two of them particularly gory (I have noticed that I have a penchant for gouging out eyes). These scenes and the one sex scene I have written were the certainly the hardest writing I’ve ever done. I essentially had to go back and read several other scenes by different writers, and borrow details from them, making them fit my own style and plot needs.

FYI: If anyone’s interested, my first fight scene is in the story “Misdirection” found in my fiction collection, Emily’s Stitches: The Confessions of Thomas Calloway (my first sex scene is also in that collection). My second fight scene is the fistfight between Ardiss Drake and Lancaster

O’Loch in the first

Guns of the Waste Land novella. The third fight scene is a Comanche attack I wrote last week for the second

Guns of the Waste Land novella.

Kirton

Yes, and I've actually written it. It came about as a result of a conversation with a female friend who said she believed pain was an essential part of sexual gratification. I didn't find her argument all that convincing because to me it sounded like the old joke about banging your head against a wall in order to feel how good it was when you stopped. Nonetheless, I wrote a scene (not a complete story) to test whether she found it palatable. It was set in a hotel room where the lovers (and they did love one another) met. There was champagne, roses, all the clichés, and I twisted them into the actual implements he used to hurt her. It was way beyond anything I'd ever dream of publishing but I made it as realistic as I could, including not allowing him to get any pleasure out of it and doing things which were against his nature but which she claimed she wanted. In the end, my friend said it was a true reflection of what she meant but that it had gone too far in one or two places. More interestingly, I didn’t like myself for having written it. It suggested that there are muddy layers in me which I’d rather not know about.

Logan

No.

Strickland

How about this one: A guy, trying to escape some great evil, plunges through a door. It leads to a slide, like a kiddie playground slide, but it’s steep and long. I mean it goes down for like fifty floors of a skyscraper. And before he reaches the end of the first ten, he becomes aware that he’s balanced on the thing, but it’s rapidly becoming narrower…and then he sees that just below it narrows to a razor edge….

9) Now, for the reverse. Is there any scene or passage, in any book or film, that you feel was either wrongly done...or something that should have been scrapped? Why?

Blake

About 90% of what Hollywood puts out if formulaic crap that should be flushed. I mean, I get the wisdom of making blockbusters that appeal to males 15-25 who have IQs slightly above that of sand who wish for nothing but thinly disguised violent morality tales featuring the toys they played with as children come to life, but is the human condition any better for it? I can't really go into detail of what's wrong with filmmaking by committee as it would take a book, but yikes. Easier to call out guys who do it right as there are so few. Tarantino being top of my list.

Bouchard

Absolutely; several, in fact. I've always been a proponent of realism and the genres which I generally

read are those with stories which could in fact happen. However, once in a while, authors have managed, inadvertently or otherwise, to include elements or scenes which caused me to shake my head and say, “Really?” Without naming names, I will specify I’m speaking of big time, traditionally published authors who, in my opinion, committed these faux-pas. For example, I have difficulty accepting a character getting a shotgun blast to the side of the face followed by a .38-caliber bullet to the chest… and surviving, particularly because his massive pecs stopped the slug. This second one is even funnier. The killer is driving a car-jacked taxi in NYC. A hostage is in the passenger seat and, behind the protective screen, two young boys are tied up on the floor in the back. The killer pulls to the curb and somehow manages to wrap himself and his three hostages into a four-man bundle with explosive cord before exiting the vehicle.

Butts

I can’t really think of one, no. Though I have been reading some early Westerns (like 1880’s and earlier) and some of those fights seem overly simplistic and too cartoonish.

Kirton

There’s one stand-out image that’s stayed with me for many years. I couldn't say it was wrong or misplaced, but its impact was such that it resonated through the rest of the film and got in the way of whatever ‘meaning’ was supposed to be there. The film opens with a man sharpening and testing a razor. We then see him holding a young, expressionless woman, who’s staring straight ahead. His fingers hold her left eye open then there’s an awful close-up of the razor slitting open the eyeball, causing stuff to spill out of it. It is, of course, the opening of the surrealist film

Un Chien Andalou by Bunuel/Dali. I remember nothing of the rest of the film, but merely recalling that cut brings back the shivers. Whatever the intention, it was so gross and so powerful that it overwhelmed everything that followed it.

Logan

In the 2005 Australian horror film,

Wolf Creek, there is a scene where Mick Taylor, played by John Jarratt…well, perhaps I’ll just quote this from the film’s wiki entry:

“Liz…gets into a car and attempts to start it, but Mick shows up in the back seat and stabs her through the driver's seat with a large knife. After more bragging, he hacks three of Liz's fingers off in one swipe, then picks her up and headbutts her into near unconsciousness. He then severs her spinal cord with a knife, paralyzing her and rendering her a "head on a stick." Mick then proceeds to interrogate her as to Kristy's whereabouts.

It felt wrongly handled when I watched it, so I looked it up online and saw that may people had walked out of the cinema during the original screenings. The film was also ambiguously marketed as being ‘based on true events’; the plot bore elements similar to the real-life murders of tourists in Australia by Ivan Milat in the 1990s and by Bradley Murdoch in 2001.

So, not just “violence porn” placing a young female character in a very prolonged and hopeless position of torture/horror/humiliation/mutilation/physical destruction, but trying to connect up this “fiction” “generically” with true-life murders that bear no real relation, in terms of specifics or persons.

Strickland

There’s stuff I haven’t liked, but that’s not quite what you’re asking. I saw the first

Night of the Living Dead ages ago in a theater, and some of the cannibalistic scenes I thought were not well-done, not because they were gross, but because they grew repetitive and the shock dulled off. In my own brief film career I appeared as an extra in a low-budget horror flick entitled

Blood Salvage in the U.S. and

Mad Jake in Europe. The plot involved a backwoods mechanic and his two deranged sons; they would sabotage cars passing through their small town, tow them into their shop, and then abduct the drivers and passengers and…raid the passengers for spare parts. Kidneys, livers, lungs, and so on. And they’d keep the mutilated victims alive as long as possible by hooking them to mechanical equivalents for their missing organs, Rube Goldberg devices cobbled together from used-car parts.

So okay, the bit I didn't care for…there’s a brief tour through the barn where all the semi-living victims are lying moaning and pleading for death. It is unsettling. And the camera pans past…Elvis, hooked to a radiator and a jukebox.

The goofiness mixed with the horror wasn't even camp. It was just somewhere way out in the woods.

10) Knights' call. Choose your own last question--and a wild, signature answer.

Blake

Question: Is violence in art something that should be regulated or censored to fit societal mores?

Answer: Well, hmm. I like to think of all markets as weighing machines. The job of artists, who are basically entertainers, is to entertain. If a society finds something like graphic violence to be titillating, it will vote with its wallets. I deeply dislike the idea of curators or gatekeepers deciding what society should and shouldn't see for its own good. As an example, I believe that TV viewers in the U.S. should be able to see children with their legs blown off, half their heads splattered against a tree, in pools of their own blood, as a result of one of our bombing runs. By sanitizing the world for the good of society, we make palatable that which is essentially unpalatable. War is now a series of cool explosions and guided missiles we can watch from the comfort of our armchair. But that's a lie. War is ugly and brutal and awful and should be avoided at all costs, because it's the ultimate expression of our failure as a species to think our way through problems. We sanitize it so it's softened, comfy, it becomes easier to justify and support. Go back and look at the grim determination of wartime photos of generals from WW1 and WW2, and contrast them to the smiles and waves of our current breed of leaders, none of whom has ever been in a trench. Nobody was happy about having to go and take human life back then, and now it's almost like watching sports for some, where there's "our team" and "them" and we're hopeful ours kills the bastards. Taking human life is horrific, and I don't think that simplifying it to sanitized sound bites does any of us good service. Anything we can do to bring that reality home, might make it way harder to "support our troops" and wave flags and cheer at our superiority, but who cares? Is our job as entertainers really to gloss over the unpleasant and make ugly behavior more palatable, to rationalize our own brutality so we feel better about it? So no, I don't think violence should be censored to protect the children or anyone else, because in the end, the world is and has always been a violent, unpredictable place where bad shit can and does happen, and to portray it as anything but that makes performing unmentionable acts easier. So you want to portray a gang hit popping a cap into a competitor on the news? Fine. Show the suffering that goes with it, the family affected by it, the destruction of lives that's reality, the blood and guts and agony and horror that is the reality of it. Censor it and you turn life into a cartoon, and turn consumers of the entertainment into overfed adult children who believe everything's round edges and characters that drop off cliffs only to pop up unharmed in the next scene.

Bouchard

Question: If you had come to the world as Theodor Seuss Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, would you have still been inclined to write crime thrillers and, if yes, can you give us a sample of what your prose would have been like?

Answer: I definitely would have written crime thrillers as Dr. Seuss. Consider the following sample of an actual passage from Vigilante, my first novel, rewritten à la Seuss:

The blow had knocked old Myers out

And sent him to the ground.

When he awoke, he was bound and gagged.

He couldn't make a sound.

His mind was dull, his skin felt wet,

And his face really hurt.

When he wiped his chin upon his shoulder

There were bloodstains on his shirt

He raised his head and saw the man,

Looking quite serene,

Standing there behind the couch

As he browsed a magazine.

“Ah, there you are,” the intruder said.

“I think that’s really great.

“I was hoping you wouldn't sleep too long,

“I don’t want to get home too late.”

The man strolled up to Myers

And gave him a cheerful grin.

“I hope you will forgive me

“For the sorry state you’re in.”

“But what you did to Mrs. Slater

“Wasn’t really nice at all.

“You know she'll never walk again

“Because of that nasty fall.”

“I was thinking you should fall down stairs

“But you really deserve much more.

“That’s why I find it practical

“That we’re up on the sixth floor.”

The man walked to the balcony

Surveying the dark parking below.

He was satisfied to see nobody

No witnesses for the show.

He returned into the apartment

Where Myers struggled on the floor.

He kicked Myers in the abdomen,

Causing Myers to resist no more.

Flinging Myers over his shoulder,

He carried him to the railing.

“Say bye-bye, Peter,” he whispered,

Then sent old Myers sailing.

Down six storeys went Myers,

Landing with a thud.

He lay there as he merited,

Dead in his own blood

Butts

Question: Given my previous answer, I want to talk a bit about slapstick and cartoonish violence. Why does ti work when done well?

Answer: I think it can be effective if used consciously (I think the poor quality of early Western violence lies in a lack writing talent, more than a misuse of cartoon violence). This type of violence is used for comic effect, and it taps into mankind’s natural tendency for schadenfreude. As a species, we do delight in the misfortune of others, especially if those others deserve it. Wile E. Coyote, The three Stooges, even Fred Flintstone, are all kind of jackasses, so the violence that happens to them appeals to our sense of justice.

We also enjoy slapstick when it makes others seem foolish in exactly the way that we have felt foolish ourselves. We laugh at the kid who drops his lunch tray or trips over a banana peel because we’re glad it isn’t us. Because it very well could’ve been us, and almost certainly will be us some time.

Kirton

Question: Could you give us an example of a refined, sophisticated use of violence to convey character and reach the highest peaks of literary excellence and linguistic perfection?’

Answer: In my book, The Sparrow Conundrum, a policeman has rigged his hotel room so that, if anyone tries to enter it, a series of pulleys will trap them under a heavy wardrobe and a bed. Two agents, code names Kestrel (who’s disguised as a maid), and Eagle, know nothing of this, creep in and are trapped. The policemen, Lodgedale, returns in his customary bad mood. Now read on.

Eagle and Kestrel heard the door bang open and their screams became babbles of relief and pleas for help. The relief, of course, was short-lived. Lodgedale noted with satisfaction the heap of bed and wardrobe and with glee the four legs sticking out from under it.

One pair of legs was trousered but the other was bare and seemed to belong to a maid. Lodgedale, ever alert, bent to look at the maid’s crotch and was surprised at how pronounced her mons pubis was. Surprise quickly became suspicion however, and he decided the maid’s gender must be checked.

There were various methods available to him but he stayed in character and aimed a kick at her crotch. Kestrel, whose scrotum was, of course, the target, exploded in areas of pain he’d never before suspected. Like all experimenters, Lodgedale repeated his test in order to verify his first set of results, was equally pleased at the outcome and turned his attention to the trousered crotch which he decided to use as a control group. Eagle’s previous delights had been derived from masochistic fantasies but no stretch of his distorted imagination could interpret the present experiences as pleasurable and the volume of his screaming matched that of Kestrel.

After only a brief period of such gratuitous violence both men fainted and Lodgedale, deprived of the satisfaction of hearing their screams, reluctantly decided to stop and try to discover who they were and why they’d entered his room.

Logan

Question: In the 1975 (again) dystopian sports action science fiction film, Rollerball, directed by Norman Jewison and starring James Caan, set in a 2018 global corporate state, is Rollerball, the violent, globally-popular sport which the then-futuristic society is so enthralled by (just as Roman citizens were once enthralled by the butchery and murderous spectacle of the first century colosseum)…is Rollerball a spectacle which brings about healthy cathartic release in the audience, or is it a spectacle which hypnotizes them and transfixes them into forgetting the underlying violence they are immersed in during their real daily lives, or is Rollerball a spectacle which hardens and desensitizes the crowd to ever-increasing levels of violence…as the crowd becomes ever more bloodthirsty and the rules of the game are incrementally changed to allow greater and greater violence, until James Caan’s Jonathan character refuses to kill his last living opponent and instead does a victory lap of the skate track while the crowd chants his name?

Answer: “The first man to raise a fist is the man who's run out of ideas.”

--H. G. Wells

Strickland

Question: If you could have written a book or script that someone else did, one that involves this kind of violence, what would it be, and why? Do you think you could have done a better job? Tell us about it!

Answer: For me—Well, remember Michael Shea, who passed away about a year ago? His

Nifft the Lean got to me on a visceral level. That’s one I can point at and say, “Man, I wish I’d had the guts and the obsessive imagination to write that.”

However, I could not have done a better job. It would take someone with a different psyche from me to beat Shea at that game, but man, I wish I had the inspiration, the twisted vision, and the courage to pull of something like that story.

******